Six months from now, a commemoration of the long saga of struggle against national oppression and economic exploitation will take place.

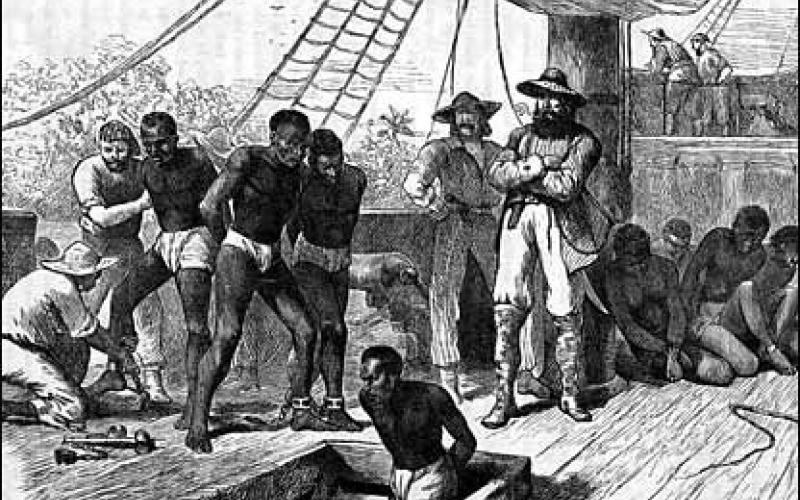

In late August of 1619, approximately 20 Africans were brought to the shore of Jamestown Settlement in Virginia, then a colony of Britain, having been captured by Portuguese colonisers in the Ndongo and Kongo kingdoms (in the vicinity of modern day Angola, Republic of Congo-Brazzaville and the Democratic Republic of Congo) and then stolen again en route to Vera Cruz on the coast of Mexico by British traders operating a warship flying a Dutch flag for the purpose of labour exploitation.

After being marched 100-200 miles (160-320 kilometres) from inland West-Central Africa, the 350 captives were loaded at the slave-port of Luanda on to the vessel San Juan Bautista. The British traders attacked the San Juan Bautista near its destination and took 50-60 Africans placing them on the White Lion and Treasurer ships directed towards Virginia where these vessels initially landed at Point Comfort (Hampton today)[[i]].

It has been reported that the majority of Africans arriving on the White Lion were acquired by wealthy British planters including Governor Sir George Yeardley and Abraham Piersey. At this time there appeared to have been no specific laws related to enslavement in the colony.

Nonetheless, these Africans could not have been considered as indentured servants since after 1640 their terms of enslavement were extended. By 1660 in Virginia the slave status of Africans brought to the colony for the purpose of servitude was made permanent.

The Treasurer, which arrived at Point Comfort several days later in August 1619, possibly unloaded seven to nine Africans, and quickly left setting sail to the Caribbean island of Bermuda. Records kept by British colonialists indicate that by March 1620, 32 Africans were living in the colony of Virginia scattered throughout homes and plantations around the James River Valley.

Over the next century-and-a-half when the European inhabitants of the 13 British colonies revolted against colonial rule and established the United States (1776-1783), the first census taken in 1790 revealed that nearly 700,000 Africans were living in slavery. The former colonies which had the largest number of enslaved Africans were four states which had more than 100,000 people in bondage in 1790: Virginia (292,627); South Carolina (107,094); Maryland (103,036); and North Carolina (100,572).

By 1860 on the eve of the Civil War (1861-1865) nearly four million Africans were living in slavery while some 500,000 were considered legally free. Most of these free Africans were still subjected to national oppression and racial discrimination many being denied the right to vote and own property, with some exceptions.

Of course African slavery can be traced back even further in the region now known as North America. The Spanish colony of Florida engaged in this economic system dating back until at least 1563 [[ii]].

Spain and Portugal were the first two European states to engage in the capturing and enslavement of Africans dating back to the 15th century. According to one source: “Just as Castilian concessions in 1479 helped put Isabel on the throne of Castile, similar recognition of Portuguese claims in Africa in 1494 helped to secure Spanish interests in the Americas. As a result, it was Spain, rather than Portugal, that first made extensive use of enslaved Africans as a colonial labour force in the Americas.”[[iii]]

Slavery, colonialism and the destruction of Black civilisations

Africans were not brought to the Americas as enslaved persons. There have been many studies, which documented the existence of civilisations and high cultures that refute the attempts to justify European domination through unscientific claims of inherent inferiority. [[iv]]

All along the West and East coasts of the continent into the interior there was the consolidation of kingdoms, city-states and nation-states. Many of these civilisations are popularly known as Ghana, Mali, Songhay, Ile-Ife, Kongo, Ndongo in the west and central interior extending north and east into Nubia, Egypt, Axum, the Swahili Coast, Zanzibar, Mutapa (Zimbabwe), Zululand, Basutoland, etc. [[v]]

The Atlantic Slave Trade represented the beginning of the systematic destabilisation of African societies. Resistance to enslavement and colonisation was a consistent theme within African history from the 15th to the 19th centuries. [[vi]]

It would take four centuries of European capitalist intervention to set the stage for widespread colonial rule across the continent. During this period long established kingdoms and cultures were decimated which dislocated millions setting the stage for further exploitation and oppression.

Eric Williams documented that the link between the transformations of mercantilism into industrial capitalism was dependent upon the profits accrued from the slave trade. In the areas of banking, commerce, shipping and mass production of commodities the burgeoning economy of Britain would lay the foundation for industrial capitalism on a monopoly scale. [[vii]]

Inside the United Sates itself the rise of the cotton industry fuelled the capitalist production outlets in the northern non-slave holding states after the early 19th century, intensifying the demand for slave labour supplied by the African people. W.E.B. Du Bois wrote on the indispensable role of African labour in the building of the United States into an industrial power by the conclusion of the Civil War. [[viii]]

With the aftermath of the eras of slavery and colonialism, Africa was placed in a position of dependency in regard to the imperialist system. The international division of labour, trade and economic power was controlled by the Western European states and the United States. Walter Rodney addressed both the character of African societies and their impact by imperialist nations. The development of Europe was a direct result of the exploitation of Africa. [[ix]]

National oppression required a repressive state apparatus to ensure the perpetuity of the capitalist system. Even after the conclusion of the Civil War and a brief period of Reconstruction, violent attacks on the African American people both judicially and extra-judicially, were designed to keep the former enslaved in line with the objective of the exploitative system.

“The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States” written by anti-lynching crusader and journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett in 1895 represented the first social scientific study of the phenomenon of state-sanctioned racial terrorism directed against African Americans during the post-Civil War years through the later decades of the 19th century. Thousands of African Americans were lynched in these years and this level of repression and brutality continued into the first half of the 20th century. [[x]]

Even today in the 21st century, African Americans are disproportionately incarcerated in penal institutions, they are affected way out of proportion to their presence in the general population by police brutality and other forms of bigoted violence by hostile forces, as well as suffering from the ravages of the capitalist system in the modern period where the gap between rich and poor inside the United States and the world is widening.

2019: The year of return

Acknowledgements of the 400th anniversary of the enslavement of Africans in Virginia have also been recognised by the West African state of Ghana where many people were captured and taken into bondage. The current President of the country, Nana Akufo-Addo, has welcomed Africans in the diaspora to visit and even relocate to Ghana this year.

This is by no means a novel idea. The founder of modern Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah, who was the first Leader of Government Business, Prime Minister and President of the First Republic from 1951-1966, maintained an open door policy towards Africans born in the West.

One fundamental distinction under the Nkrumah government was that it was categorically committed to the realisation of Pan-Africanism by the establishment of a continental government. Nkrumah was also a socialist and anti-imperialist realising that the acquisition of national independence was only the first step in bringing about the total liberation, unification and social emancipation of Africans. Moreover, that this movement towards the socialist unification of Africa was part and parcel of the world movement against imperialism.

A historical correction of the social impact of centuries of slavery, colonialism and neo-colonialism requires much more than a symbolic gesture. Africans both on the continent and in the diaspora are still being subjected to capitalist exploitation.

In fact the world economic system remains a reflection of the material legacy of the rise and dominance of European imperialism over the last six centuries. This current international situation requires a fundamental shift in the nature of global relations along with the creation of structures, which can guarantee freedom and justice for those victimised by institutional oppression and exploitation.

* Abayomi Azikiwe is Editor at Pan-African News Wire

Endnotes

[i]https://historicjamestowne.org/history/the-first-africans/accessed on 24 February 2019

[ii]https://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/taro/utcah/02980/cah-02980.html#a0accessed 24 February 2019

[iii]http://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/african_laborers_for_a_new_emp/the_spanish_and_new_world_slavaccessed 24 February 2019

[iv](http://www.centerformaat.com/files/African_Origin_of_Civilization_Complete.pdf) accessed 24 February 2019

[v]https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/326812/africans-and-their-history-by-joseph-e-harris/9780452011816/accessed 24 February 2019

[vi]https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/1682348accessed 24 February 2019

[vii]https://archive.org/stream/capitalismandsla033027mbp/capitalismandsla033027mbp_djvu.txtaccessed 24 February 2019

[viii]http://ouleft.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/blackreconstruction.pdfaccessed 24 February 2019

[ix]http://abahlali.org/files/3295358-walter-rodney.pdfaccessed 24 February 2019

[x]https://archive.org/stream/theredrecord14977gut/14977.txtaccessed 24 February 2019

- Log in to post comments

- 11746 reads